Weaving together cultural criticism, personal narrative, historical diversions, and on-the-ground research, MAKE ME FEEL SOMETHING is a search for pure, loud, vibrant sensory experience and the knowledge that can only come from that source.

MAKE ME FEEL SOMETHING:

In Pursuit of Sensuous Life in the Digital Age

by Jennifer Schaffer-Goddard

Ecco/HarperCollins, Summer 2024

(via Sterling Lord Literistic)

As physical life on earth grows increasingly fraught and imperiled, technology moves to take us out of our bodies and into our screens. Capital is flooding into the development of the metaverse, designed to engulf us even more fully in tech’s trackable, commodifiable sphere.

As physical life on earth grows increasingly fraught and imperiled, technology moves to take us out of our bodies and into our screens. Capital is flooding into the development of the metaverse, designed to engulf us even more fully in tech’s trackable, commodifiable sphere.

And as the influence of these newly manufactured modes of experience promises to grow more fixed and invasive, it is not hyperbole to suggest that the years ahead will require us to reckon with questions that, at first glance, may seem surreal: What is the point of physical life? What are our bodies for?

Although we are saturated by an overload of stimuli, we engage with our actual physical senses—touch, taste, sight, scent, and sound—less and less. It’s no surprise we face an epidemic of depression and disassociation; no wonder that, in an era that demands engagement, we often find ourselves numb, forgetful, and detached. We need an urgent and necessary alternative: a return to the vital purpose and pleasure of our embodied senses.

This is precisely the mission of MAKE ME FEEL SOMETHING, a multi-hyphenate work of narrative non-fiction offering a radical reappraisal of the five senses in our break-neck technological world, as well as our sense of time, place, and of self.

With the improbably intermingled properties of Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing, Samin Nosrat’s Salt Fat Acid Heat, and John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, MAKE ME FEEL SOMETHING is a personalized, thematically anchored quest narrative that proposes a defiant way forward for sensory life.

Jennifer Schaffer-Goddard was born in Chicago in 1992, the year Apple declared handheld devices would change the world. A 2021 finalist for the Krause Essay Prize, her work has appeared in The Nation, The Baffler, The Paris Review Daily, Vulture, The Times Literary Supplement, The Idler, The White Review, The New Statesman, and elsewhere in print and online. Her research on the societal impacts of artificial intelligence has received recognition and funding from the Royal Society, the Centre for the Future of Intelligence, and the Partnership on Artificial Intelligence in Cambridge and Oxford. A graduate of Stanford and the University of Cambridge, she has, for better or worse, spent several years working in the tech industry.

Thirteen essays are included that explore the evocative scents of trees, from the smell of a book just printed as you first open its pages, to the calming scent of Linden blossom, to the ingredients of a particularly good gin & tonic. In your hand: a highball glass, beaded with cool moisture. In your nose: the aromatic embodiment of globalized trade. The spikey, herbal odour of European juniper berries. A tang of lime juice from a tree descended from wild progenitors in the foothills of the Himalayas. Bitter quinine, from the bark of the South American cinchona tree, spritzed into your nostrils by the pop of sparkling tonic water. Take a sip, feel the aroma and taste of three continents converge.

Thirteen essays are included that explore the evocative scents of trees, from the smell of a book just printed as you first open its pages, to the calming scent of Linden blossom, to the ingredients of a particularly good gin & tonic. In your hand: a highball glass, beaded with cool moisture. In your nose: the aromatic embodiment of globalized trade. The spikey, herbal odour of European juniper berries. A tang of lime juice from a tree descended from wild progenitors in the foothills of the Himalayas. Bitter quinine, from the bark of the South American cinchona tree, spritzed into your nostrils by the pop of sparkling tonic water. Take a sip, feel the aroma and taste of three continents converge. After living through the massive global shock and trauma of Covid-19, one of the most disruptive events in human history, we need to find a way to face the future with optimism. But how can we plan for a better future when it feels impossible to predict what the world will be like next week, let alone next year or in the next decade? What we need are new tools to help us recover our confidence, creativity, and hope in the face of an uncertain future. In Imaginable, world-renowned future forecaster and game designer Jane McGonigal draws on the latest scientific research in psychology and neuroscience to show us how to train our brains to think the unthinkable and imagine the unimaginable. Using gaming strategies and fun, thought-provoking challenges that she designed specifically for this book, she helps us build our collective imagination to dive into the future before we live it and envision, in surprising detail, what our lives will look like ten years out.

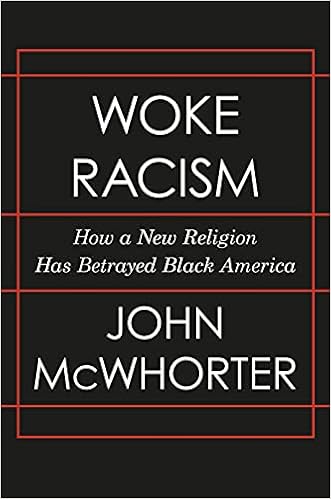

After living through the massive global shock and trauma of Covid-19, one of the most disruptive events in human history, we need to find a way to face the future with optimism. But how can we plan for a better future when it feels impossible to predict what the world will be like next week, let alone next year or in the next decade? What we need are new tools to help us recover our confidence, creativity, and hope in the face of an uncertain future. In Imaginable, world-renowned future forecaster and game designer Jane McGonigal draws on the latest scientific research in psychology and neuroscience to show us how to train our brains to think the unthinkable and imagine the unimaginable. Using gaming strategies and fun, thought-provoking challenges that she designed specifically for this book, she helps us build our collective imagination to dive into the future before we live it and envision, in surprising detail, what our lives will look like ten years out. Americans of good will on both the left and the right are secretly asking themselves the same question: how has the conversation on race in America gone so crazy? We’re told to read books and listen to music by people of color but that wearing certain clothes is “appropriation.” We hear that being white automatically gives you privilege and that being Black makes you a victim. We want to speak up but fear we’ll be seen as unwoke, or worse, labeled a racist. According to John McWhorter, the problem is that a well-meaning but pernicious form of antiracism has become, not a progressive ideology, but a religion—and one that’s illogical, unreachable, and unintentionally neoracist.

Americans of good will on both the left and the right are secretly asking themselves the same question: how has the conversation on race in America gone so crazy? We’re told to read books and listen to music by people of color but that wearing certain clothes is “appropriation.” We hear that being white automatically gives you privilege and that being Black makes you a victim. We want to speak up but fear we’ll be seen as unwoke, or worse, labeled a racist. According to John McWhorter, the problem is that a well-meaning but pernicious form of antiracism has become, not a progressive ideology, but a religion—and one that’s illogical, unreachable, and unintentionally neoracist. These new and collected essays from the acclaimed naturalist Barry Lopez—his final undertaking—represent the culmination of a lifetime’s thought in service of our relationship with wilderness, and with each other. Here, his collected essays offer a unifying vision; his drive to reconnect the cultural and the natural is unflinching, and major, never-published pieces offer profound commentary on topics that veer from the autobiographical—his abuse as a child—to the evolution of his views on the untamed. His classic prose, like the arctic landscape he elegized, remains as ever: “spare, balanced, extended…” It has been said that Barry Lopez understood what we gain when we accept the enormity of what we don’t know; these essays hinge on that tantalizing concept.

These new and collected essays from the acclaimed naturalist Barry Lopez—his final undertaking—represent the culmination of a lifetime’s thought in service of our relationship with wilderness, and with each other. Here, his collected essays offer a unifying vision; his drive to reconnect the cultural and the natural is unflinching, and major, never-published pieces offer profound commentary on topics that veer from the autobiographical—his abuse as a child—to the evolution of his views on the untamed. His classic prose, like the arctic landscape he elegized, remains as ever: “spare, balanced, extended…” It has been said that Barry Lopez understood what we gain when we accept the enormity of what we don’t know; these essays hinge on that tantalizing concept.