L’Académie royale des sciences de Suède vient de décerner le prestigieux prix Crafoord 2022 dans la catégorie Géosciences à Andrew Knoll « pour les contributions fondamentales qu’il a apportées à notre compréhension des trois premiers milliards d’années de la vie sur Terre et des interactions du vivant avec l’environnement physique au fil du temps. » Ce prix, qui vise chaque année à promouvoir certaines disciplines scientifiques à travers le monde depuis 1982, est considéré comme un complément, voire dans certains cas un prix annonciateur, du Nobel. Il est accompagné d’une récompense de six millions de couronnes suédoises, soit plus de cinq cent mille euros.

L’Académie royale des sciences de Suède vient de décerner le prestigieux prix Crafoord 2022 dans la catégorie Géosciences à Andrew Knoll « pour les contributions fondamentales qu’il a apportées à notre compréhension des trois premiers milliards d’années de la vie sur Terre et des interactions du vivant avec l’environnement physique au fil du temps. » Ce prix, qui vise chaque année à promouvoir certaines disciplines scientifiques à travers le monde depuis 1982, est considéré comme un complément, voire dans certains cas un prix annonciateur, du Nobel. Il est accompagné d’une récompense de six millions de couronnes suédoises, soit plus de cinq cent mille euros.

Pour plus d’informations, voir le communiqué de presse sur le site officiel.

Andrew Knoll est professeur à Harvard dans les départements de Biologie organismique et évolutive et des Sciences de la terre et des planètes. Il a notamment travaillé sur les microfossiles et développé des méthodes innovantes pour mettre en lumière leur évolution biochimique. En outre, il est l’un des chercheurs ayant présenté une explication probable à la troisième extinction de masse, qui s’est produite il y a 252 millions d’années – elle aurait été due à des éruptions volcaniques en Sibérie ayant provoqué l’émission d’énormes quantités de dioxyde de carbone dans l’atmosphère et entraîné une augmentation de la température moyenne sur Terre. Depuis vingt ans, Andrew Knoll fait également partie de l’équipe de recherche qui aide la NASA à analyser les images et autre données géologiques provenant de Mars.

Andrew Knoll est professeur à Harvard dans les départements de Biologie organismique et évolutive et des Sciences de la terre et des planètes. Il a notamment travaillé sur les microfossiles et développé des méthodes innovantes pour mettre en lumière leur évolution biochimique. En outre, il est l’un des chercheurs ayant présenté une explication probable à la troisième extinction de masse, qui s’est produite il y a 252 millions d’années – elle aurait été due à des éruptions volcaniques en Sibérie ayant provoqué l’émission d’énormes quantités de dioxyde de carbone dans l’atmosphère et entraîné une augmentation de la température moyenne sur Terre. Depuis vingt ans, Andrew Knoll fait également partie de l’équipe de recherche qui aide la NASA à analyser les images et autre données géologiques provenant de Mars.

Son livre A BRIEF HISTORY OF EARTH est paru en avril 2021 chez Custom House aux États-Unis. Les droits de langue française sont toujours disponibles.

Liste des cessions étrangères :

Chine (Ginkgo)

Corée (Dasan)

Espagne (Ediciones Pasado&Presente)

Estonie (Julius Press)

Grèce (Psichogios)

Hongrie (Open Books)

Italie (HarperItalia)

Japon (Bunkyosha)

Pays-Bas (Thomas Rap/Bezige Bij)

Pologne (Copernicus Center Press)

Portugal (Saida D’Emergencia)

Roumanie (Litera)

Russie (Portal Publishing)

Slovaquie (Albatros Slovakia)

Thaïlande (Amarin)

Turquie (Ayrıntı)

A global pandemic, economic volatility, natural disasters, civil and political unrest. From New York to Barcelona to Hong Kong, it can feel as if the world as we know it is coming apart. Through it all, our human spirit is being tested. Now more than ever, it’s imperative for leaders to demonstrate compassion. But in hard times like these, leaders need to make hard decisions—deliver negative feedback, make difficult choices that disappoint people, and in some cases lay people off. How do you do the hard things that come with the responsibility of leadership while remaining a good human being and bringing out the best in others? Most people think we have to make a binary choice between being a good human being and being a tough, effective leader. But this is a false dichotomy. Being human and doing what needs to be done are not mutually exclusive. In truth, doing hard things and making difficult decisions is often the most compassionate thing to do.

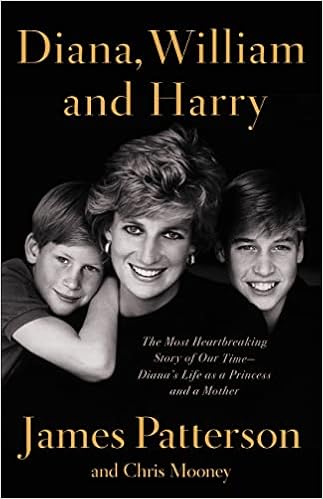

A global pandemic, economic volatility, natural disasters, civil and political unrest. From New York to Barcelona to Hong Kong, it can feel as if the world as we know it is coming apart. Through it all, our human spirit is being tested. Now more than ever, it’s imperative for leaders to demonstrate compassion. But in hard times like these, leaders need to make hard decisions—deliver negative feedback, make difficult choices that disappoint people, and in some cases lay people off. How do you do the hard things that come with the responsibility of leadership while remaining a good human being and bringing out the best in others? Most people think we have to make a binary choice between being a good human being and being a tough, effective leader. But this is a false dichotomy. Being human and doing what needs to be done are not mutually exclusive. In truth, doing hard things and making difficult decisions is often the most compassionate thing to do. At age thirteen, she became Lady Diana Spencer. At twenty, Princess of Wales. At twenty-one, she earned her most important title: Mother. As she fell in love, first with Prince Charles and then with her sons, William and Harry, the world fell in love with the young royal family—Diana most of all. With one son destined to be King of England, and one to find his own way, she taught them dual lessons about real life and royal tradition. « William and Harry will be properly prepared, » Diana once promised. « I am making sure of this. » Even after the shield of her love is tragically torn away, she remains their greatest protector—and the world’s enduring inspiration.

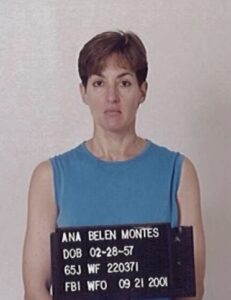

At age thirteen, she became Lady Diana Spencer. At twenty, Princess of Wales. At twenty-one, she earned her most important title: Mother. As she fell in love, first with Prince Charles and then with her sons, William and Harry, the world fell in love with the young royal family—Diana most of all. With one son destined to be King of England, and one to find his own way, she taught them dual lessons about real life and royal tradition. « William and Harry will be properly prepared, » Diana once promised. « I am making sure of this. » Even after the shield of her love is tragically torn away, she remains their greatest protector—and the world’s enduring inspiration. In the aftermath of 9/11, Ana Montes was arrested by federal authorities after 17 years of feeding American secrets to the Cuban government.

In the aftermath of 9/11, Ana Montes was arrested by federal authorities after 17 years of feeding American secrets to the Cuban government.  Email replies that show up a week later. Video chats full of “oops sorry no you go” and “can you hear me?!” Ambiguous text-messages. Weird punctuation you can’t make heads or tails of. Is it any wonder communication takes us so much time and effort to figure out? How did we lose our innate capacity to understand each other?

Email replies that show up a week later. Video chats full of “oops sorry no you go” and “can you hear me?!” Ambiguous text-messages. Weird punctuation you can’t make heads or tails of. Is it any wonder communication takes us so much time and effort to figure out? How did we lose our innate capacity to understand each other?